Deep-Learning Side-Channel Attacks

Deep learning side channel attacks involve exploiting unintended information leakage from the implementation of deep learning models to infer sensitive information or manipulate their behavior. Recently I visited a presentation by Dr. Boyang Wang from the University of Cincinnati. Below I’ll give an overview of what Dr. Wang presented about his research into deep-learning side-channel attacks and offer my own critique.

Synopsis

In general terms, “side channel attacks” are attacks that use “side channel information”, which is information that can be retrieved from an encryption device. In this project, an attacker uses a side-channel attack (SCA) to analyze power draw of a specific target when it runs encryption with the aim of recovering its encryption key. The immediate question of “why” arises. Why is this possible? This is possible because power consumption is correlated with the intermediate values of encryption. In simpler terms, when an encryption algorithm runs, more power is drawn. In even simpler terms, computing one byte with all zeros consumes less power than one byte with all ones.

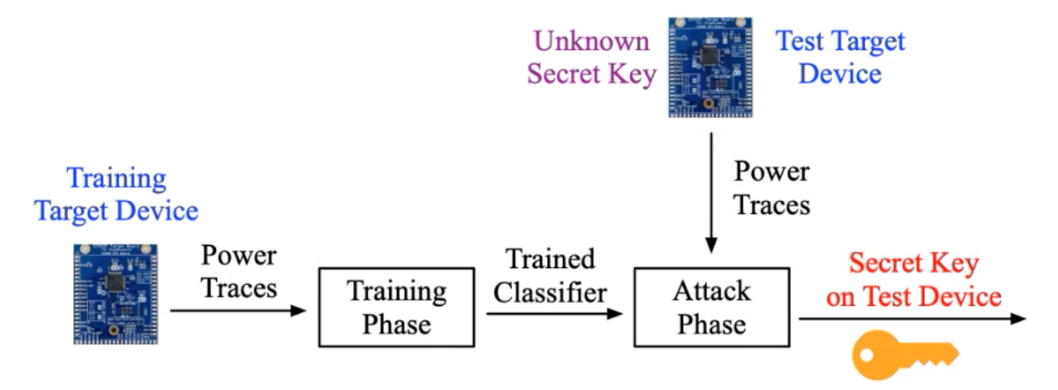

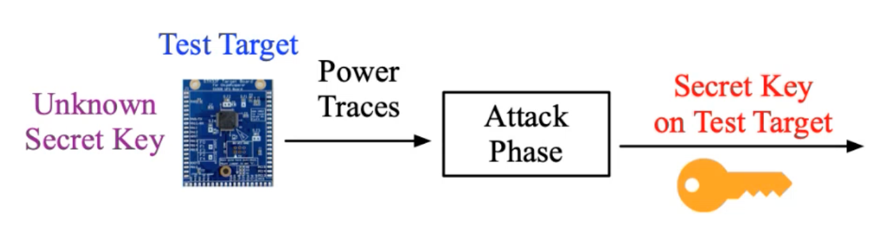

In general, SCAs can be categorized into two separate types: profiling attacks, which use a training device and a testing device, and non-profiling attacks, which only use the test device. Figure 1 below portrays profiling attacks, while Figure 2 shows non-profiling attacks.

Fundamentally, non-profiling attacks are more challenging.

Deep learning studies focusing on convolutional neural networks (CNN) so far have had mixed results, according to Dr. Boyang. This is surprising, because CNNs excel at Large Language Models (LLMs) and generative AI. Adjusting points of interest has proven to be problematic. Adjusting points of interest over test data can reveal keys, but not necessarily always, using a CNN algorithm. Domain adaptation has so far in literature resulted in most disappointing results. While it works well for images, it fails for power traces with side channel attacks. Multi-domain training proved to be reasonably successful. However, this mechanism assumes that an attacker knows all software settings in advance. This obviously represents a barrier of entry and in practical terms would be confined to an inside job.

As the results showed, once again an attacker must have a fairly large amount of domain knowledge and in some cases must also actually possess physical access identical to the test device, such as in profiling attacks. This deep learning side channel attack study contributes by optimizing problems identified with the above mitigation techniques to:

- Use TripletPower, which requires fewer traces (compared to CNN),

- Leverage triplet neural networks to learn a more robust embedding,

- Work for both profiling and non-profiling attacks (Figure 1 and Figure 2 above).

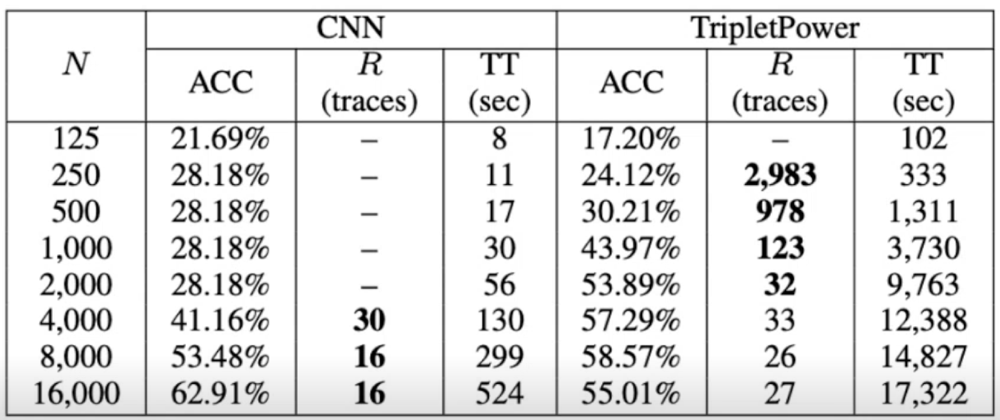

For profiling attacks (Figure 1), using TripletPower proved more favorable over using CNNs, assuming fewer training traces are available. CNN does outperform TripletPower if there are sufficient training traces available, more than 4,000 as can be seen in Figure 3 below.

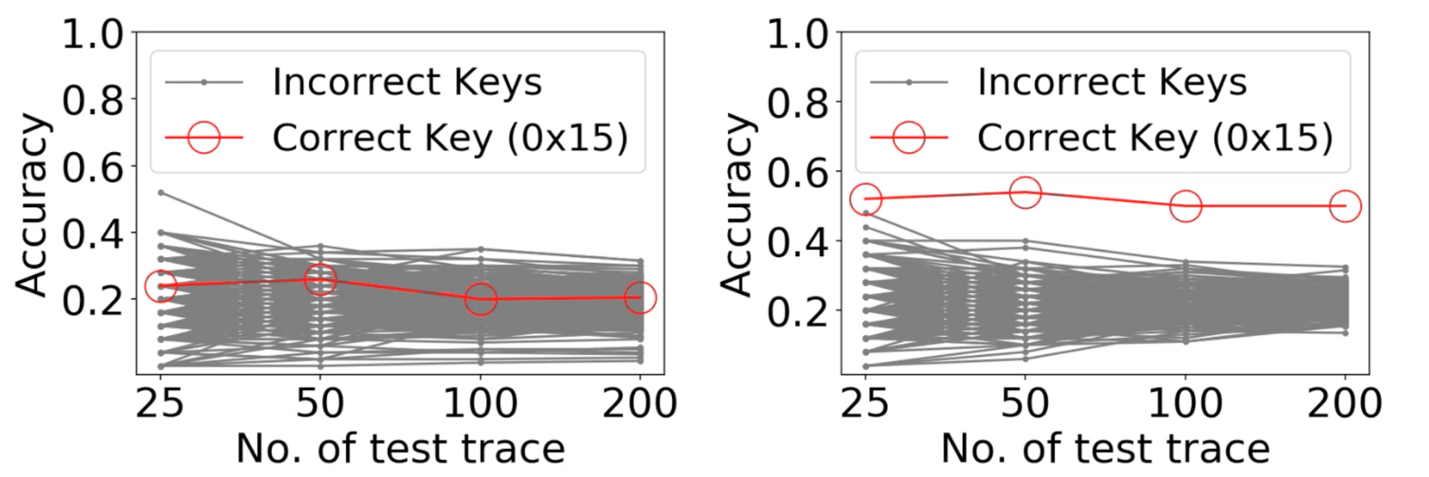

However, in practical terms, TripletPower, at least from an attacker’s perspective, does lower the barrier of entry without thousands of training traces. For profiling attacks (Figure 2), similar observations were made as can be seen in Figure 4 below. Once there are sufficient traces available, more than 500, clear encryption keys can be identified.

Critique and Challenges

This side channel attack study makes several assumptions which deserve a deeper discussion. Below I have high-lighted some challenges that should be considered and/or overcome.

Profiling Side Channel Attacks

Profiling side channel attacks make several assumptions, which increase an attacker’s difficulty and level of effort required to crack an AES encryption algorithm. This represents a huge barrier to entry which could very well deter attackers and not provide enough incentive. However, determined attackers may still go through such trouble.

Power Consumption Monitoring

This study assumes that an attacker has access to and, as a result, can indeed monitor power consumption, to target encryption processes. This represents a security risk in and of itself. Most practical applications where this would pose a threat already have mitigated or flat out prevented access to data centers, server racks, servers, and let alone individual microcontroller. This represents a huge challenge. To gain access to and monitor power consumption, a malicious actor must have already overcome numerous other fail-safes. Furthermore, other questions arise when it comes to power consumption monitoring. For example, how would batteries change the calculus for this side-channel-attack?

AES Encryption

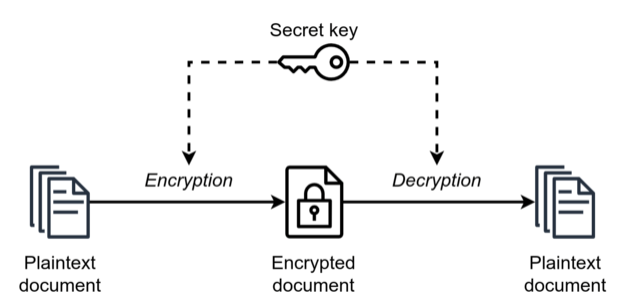

This study focuses on AES-128 encryption. AES is a symmetric-key algorithm. This means that the same key is used for both encryption and decryption. Figure 5 below illustrates this visually.

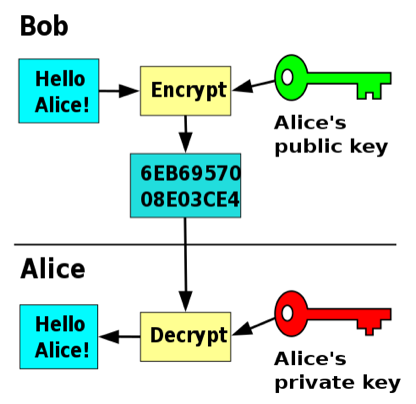

This characteristic makes side channel attacks especially worrisome. Considering this, asymmetric encryption algorithms that rely on public and private keys can mitigate risk. Figure 6 illustrates asymmetric encryption.

Examples of asymmetric encryption algorithms include Rivest-Shamir-Adelman (RSA), Digital Signature Standard (DSS), and Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA). (IBM) How do asymmetric algorithms affect side channel attacks? Do they become inadequate? Are asymmetric encryption algorithms used with target devices for side channel attacks? Or maybe asymmetric algorithms are impractical considering a private key may need to be stored on a target device? These questions could provide further research direction. Furthermore, it is absolutely true that AES-128 encryption represents a strong and robust encryption algorithm. Using brute force to crack AES-128 is practically impossible. Obviously using indirect methods such as side channel attacks work better. However, most practical, real-world applications use AES-256 encryption. It may be worthwhile to analyze and study the effects of using AES-256 encryption. Is it safe to assume that AES-256 encryption would represent an exponentially more difficult problem and it would prove too difficult to crack?